Three decades ago, while wandering through the Himalayas, I ventured from the Vale of Kashmir to Ladakh, a mountainous realm where some of the planet’s tallest peaks rise above a high plateau. Now, thirty years later, as I gaze into Deception Basin in the Olympic Mountains, the scenery is so reminiscent of Ladakh—green vegetation fringing a stream meandering through a rocky moonscape—that it feels as though a portal has opened. I find myself traveling from age 51 back to 21, as if returning to India to seek a path that leads away from the suffering inherent in all living things. Or, as the name Deception Pass suggests, am I being deceived by a mountain mirage?

The thrill of surviving with death so close was exhilarating, and the suffering felt sublime. But I’m done with that now.

My state of mind cannot be blamed on the altitude. Deception Pass is just shy of 7,000 feet above the sea, which is visible in the distance as a shade of blue darker than the sky. In the elevated heart of Asia, where I once slept on a monastery floor while learning about Buddhism and recuperating from a mountaineering expedition that had pushed me beyond my limits, I was 5,000 feet higher above sea level than Deception Pass. All of that seeking, that striving I did back then, had left me cold. I lay shivering on a stone floor, my head aching with altitude sickness as monks went about their routines, doing chores and chanting. Enlightenment seemed as distant as my hometown in Missouri, as unattainable as the summits I was not equipped to climb.

As I thanked the monks for their kindness and left Ladakh, heading off on my next adventure, a moment of clarity came to me—an epiphany of sorts: I had absolutely no idea what I was doing in Asia. After deciding that college textbooks couldn’t teach me what was worth knowing, I had headed to the Himalayas. But I realized I was no more likely to make sense of existence by studying Eastern philosophy and climbing mountains in Asia than I was while working as a security guard in a parking garage in St. Louis, a job that had paid for college. The scenery in northern India was stunning, but the best way to figure out how to live a life is, of course, to live a life.

Three decades later, not much has changed. I’m still journeying in the mountains, still seeking—if not enlightenment, at least some solace and inspiration. And I’m still stumbling my way along life’s path, trying—and generally failing—to figure out what it all means.

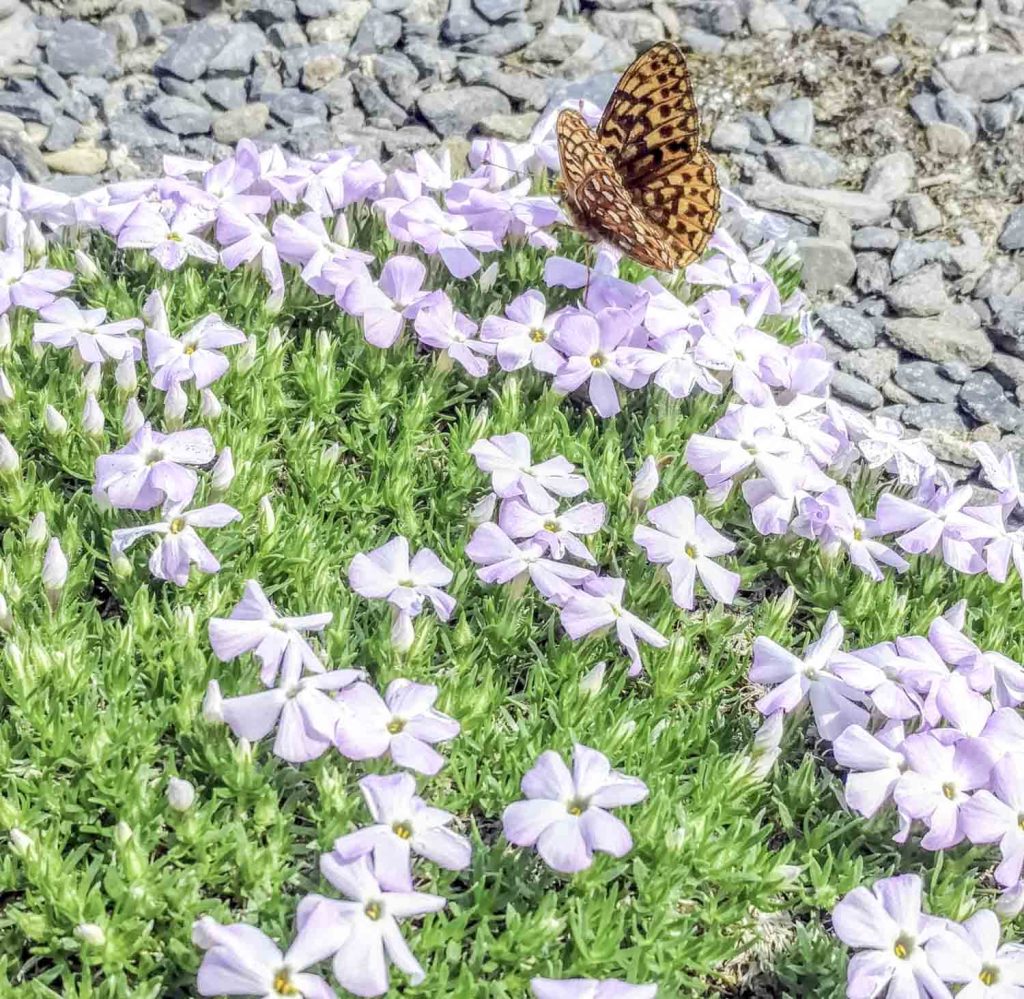

Before reaching the top of Deception Pass and catching sight of Mount Mystery, the peak that rises on the other side of Deception Basin, I glanced down at my trail-running shoes and noticed a plant that reminded me of my friend Willi Smothers. I swallowed the sadness that rose in my throat, and by the time I reached the top of the pass, a smile at the memory of what Willi had taught me stretched my wind-cracked lips. Dust settled on my tongue as the wind moved yellow blooms of Olympic Mountain Ragwort like a field of swaying suns. Seeing plants survive in such severe conditions, blooming on slopes of cold stone scoured by wind, never fails to move me. Life is fragile in the mountains, and death is always near.

But just when you start pondering lofty thoughts on a mountain pass, you remember a goat dangling from a helicopter.

One spring morning, while hiking through an alpine meadow in the Olympic Mountains, I saw a goat hanging in a sling from a helicopter. I had taken no drugs. I had not hit my head. I was neither exhausted nor starved. No hallucinations or delusions had addled my mind. My cognitive machinery seemed to be functioning as it usually does. And yet, when I looked up, a goat hung suspended in the sky.

The pilot of the helicopter flew so close that I waved at him, and he waved back. “There’s a goat hanging from your helicopter,” I shouted, as if he could hear me above the roar of the rotors. As if he didn’t know that.

The isolation of the Olympic Peninsula, surrounded by water and ice over millennia, has led to the evolution of several endemic species, such as the Olympic Marmot, which exists nowhere else in the world. This same isolation has also resulted in the conspicuous absence of other species. When European explorers entered the Olympic wilderness, they found no grizzlies, lynx, pikas, coyotes, sheep, or goats—species present in the Cascades and Rockies. Mountain goats were later introduced to the Olympics as game animals. As their population grew, these goats began to destroy native vegetation, including endemic plants of the Olympic Mountains—the plants that Willi Smothers loved. These plants grow only in the heights of the Olympic Mountains.

The introduced mountain goats became a nuisance not only to the plants in the high country but also to humans. Lacking the natural salt deposits found in other ranges where mountain goats evolved, the animals introduced to the Olympics developed a desperate craving for this essential mineral. As their numbers grew and their salt deprivation worsened, the goats became increasingly aggressive. They began harassing hikers, following them to lick their salty pee from the ground, and stealing hiking poles and boots crusted with sweat. During the rutting season, male mountain goats charged at people. One such attack was fatal: a goat severed a man’s femoral artery with a single stab of its horn, leading to the unfortunate hiker’s death. Forget bears—death by goat had become a more pressing danger in the Olympic wilderness.

A few words should be said in defense of the mountain goats. First, they did not choose to be relocated to the Olympics—it was not their decision. And although they do not naturally belong in the Olympic Mountains, these animals are still magnificent creatures. Members of the antelope family, rather than true goats, they possess burly shoulder muscles that provide impressive climbing power and deft hooves with two toes capable of independent movement. These daredevil rock climbers perform astonishing feats of agility on sheer cliff faces where predators cannot follow. I once spent a memorable hour in the Cascades watching a kid goat wander away from its nanny to frolic on a steep-sided boulder, scaling the miniature mountain with remarkable bravado. Hikers gathered on the trail to see this kid, as cute as a toy, dancing along danger’s edge while its mother grazed the grass below.

A few years ago, the National Park Service removed most of the mountain goats from the Olympic Mountains by capturing and relocating them to their native range in the Cascades. Hence, the helicopter I saw. Imagine the tales the flying goat would share upon returning to solid ground in another mountain range: “You won’t believe what just happened to me,” it might recount to its fellow mountain goats. Its story would strain the credulity of its peers. When I told my wife Amy, a healthcare professional, that I’d seen a goat dangling from a helicopter, she checked my pupils to ensure I hadn’t had a stroke.

As the mountain goats are airlifted out and the remaining holdouts are shot by well-heeled hunters who pay a small fortune to kill those that eluded helicopter capture, the plant community will start to heal. From dusty wallows and meadows trampled by cloven hooves in the Olympic high country, wildflowers will once again bloom—the native plants that Willi loved.

Some of the endemic plants in the Olympic Range are memorable not only for their rarity but also for the challenges involved in encountering them. Olympic Mountain Ragwort, for instance, might not catch your eye if it were growing on the plains below; you might dismiss it as a weed in need of removal. But context is everything. The more effort you invest in finding plants in these remote mountain strongholds, the more they captivate you. Botanizing in the Olympic Range can be extreme, demanding arduous hikes in mountains that remain only marginally less wild than when they were first visited by Indigenous people.

As the cities of Seattle and Tacoma began sprawling along the lowlands of Puget Sound, railroads did not reach the Olympic Range. The confusion of peaks that conceals the wild heart of the Olympic Peninsula remained one of the last places in the lower 48 states to be explored. Mount Olympus, the most prominent peak in the range, was named by a British fur trader who sailed along the Washington coast in 1788. He wrote, “If that not be the home wherein dwell the gods, it is beautiful enough to be, and I therefore call it Mount Olympus.”

Not everyone shared this view. Some early explorers believed that demons lurked in this terra incognita, fearing that the blank space on maps was a realm of evil. It wasn’t until 1890, when the curiosity of Seattle residents about the mountain wilderness across Puget Sound prompted a newspaper to sponsor an expedition, that Americans of European ancestry finally crossed this range.

I have seen neither gods nor demons in this wilderness of peaks that snag the clouds, but I have encountered extraordinary plants. Perhaps the most compelling of the Olympic endemics is Cut-leaf Synthyris. Though not as visually striking as Piper’s Bellflower, which boasts pale blue blooms, Cut-leaf Synthyris has a remarkable story. Like the Glacier Lily, this plant appears to generate heat to melt the spring snowpack, warming itself so it can greet the sun.

Most plants cannot raise their temperature above the surrounding air. However, some species are thermogenic, generating excess heat in their mitochondria through a process that is not fully understood. This heat may help disperse chemicals that attract pollinators. Species like Cut-leaf Synthyris appear to use this heat to blowtorch their way through the snow, extending their growing season. Because summer graces mountaintops only briefly, alpine plants are eager to bloom. Cut-leaf Synthyris may generate heat internally or melt the snow simply by being darker than the surrounding whiteness. The leaves and petals absorb sunlight and radiate it outward, helping them escape winter’s white prison.

Most of my botanizing has involved moving at such a slow pace that I’ve been overtaken by banana slugs gliding along the trail. The greatest danger on these leisurely outings is a muscle cramp from hours of bending over, and the essential gear is a hand lens. In contrast, searching for Cut-leaf Synthyris may require crampons as well as an ice axe to arrest a fall on slippery snow. After finding Cut-leaf Synthyris on a steep mountainside, you might return by glissading down a snowfield, using your ice axe as a rudder to control your exhilarating slide.

The memory of this flower you sought in hazardous places may never leave you, for the danger of “adventure botany” etches the experience deep in your brain. If this plant bloomed outside your door, you might ignore it. Paramount is the quest. And some fear makes the search more fun.

I nearly died to see a fern. One afternoon in late July a few years ago, while hiking with Willi in search of Olympic endemic plants, I crawled onto a boulder perched atop a cliff in the Olympic Mountains to look at what seemed like a fern. Before this sighting, I had assumed all ferns live in moist forests. Not so. Desert ferns have adapted to harsh drylands, I learned. They get their start as spores in fractured stone, where cracks in rocks create moist microclimates. The waxy coating, hair, or fuzz on their fronds helps conserve water, and protective scales shield the stems from dry air.

The species I encountered in a soil-seamed crack of a cliff battered by sun and wind, far from any forest, was Parsley Fern. The alpine environment seemed extreme for a fern, but after some research, I realized this habitat was relatively mild compared to deserts—and to the ash-buried wasteland of Mount St. Helens. The 1980 eruption obliterated forested slopes, annihilating countless plants and animals. “Death is everywhere,” noted the Oregonian newspaper. “The living are not welcome.” Yet, in a land so devastated it seemed nothing would ever grow again, Parsley Ferns soon unfurled, adding a touch of greenery to the gray pumice plains and moonscape lava fields. Life, defiant. Life rising from fire and ash: poetry in a frond.

The Parsley Fern thrives not only in the rocky terrain of mountaintops but also in the rainshadow of the Olympic Range, where moisture is so scarce that cacti wield their spines. Though ferns may appear delicate with their lacy fronds, they are far more resilient than one might assume. They survived the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs, not merely the lacy doilies of the plant world or frivolous decorations.

Willi pursued rare plants in high places with his partner, Janet Welch, a former park ranger who once hiked many sweltering miles deep into the Grand Canyon to rescue tourists from heat exhaustion and dehydration. Janet has not slowed down in the years since. Despite being a couple of decades ahead of Amy and me, both she and Willi were as wiry and energetic as teenagers. Their pace on mountain hikes kept us working hard to keep up with them.

Willi, besides being knowledgeable about plants, was kind. He didn’t mock me when I shouted about a fern growing from a cliff—a sight he had long since grown accustomed to. He didn’t laugh when I nearly fell while pursuing this common plant. Now, having seen many Parsley Ferns and Alpine Lady Ferns sprouting from cracks in mountain rocks, the sight of green filigree in a stony landscape still moves me. But I’ve calmed down enough to avoid going too far out on a ledge.

After my perilous encounter with the fern, I descended from the cliff and wandered into a mountain meadow to admire bouquets of Woolly Sunflower and Magenta Paintbrush. As I stooped to examine these flowers, I noticed a yellow-and-black pollinator that seemed like a bee but turned out to be a hoverfly—a clever mimic. Willi’s face lit up when I pointed out this stingless insect that evolution has disguised as a bee. His enthusiasm for seeing a hoverfly was unparalleled. With his shockingly white hair and skin etched by years of sun and salt from sailing the world’s seas, Willi approached nature with the boundless curiosity of a child.

The wildflowers in this alpine meadow were resplendent, with hoverflies and bees busily perpetuating botanical beauty on the mountaintops by moving pollen between blooms. Much like ferns, bees often appear in unexpected places. Bees and their impostors are everywhere, from the edge of the sea to the roof of the sky—even the Arctic.

A species of bumblebee with thick fur lives north of the Arctic Circle, where it builds an insulated nest to protect its body from the killing cold. This bee of the far north warms itself by basking inside blooms of the Arctic Poppy, conical flowers that concentrate sunlight as the plant turns its face throughout the day to follow the arc of the sun. My memories of mountains in Alaska make me shiver, but I cannot recall seeing bumblebees. In those days, I saw only summits. I scanned for routes on rock and ice without reading details of the living world. Whatever was worth seeking would be found by struggling to reach high places, I believed, not by slowing down to pay attention to what surrounded me.

After traveling through Alaska, Asia, Africa, and other remote regions, I worked in the dining room at Paradise Lodge in Mount Rainier National Park, where I served breakfast to my hero, Jim Whittaker, the first American to reach the summit of Mount Everest. I was too focused on becoming a mountaineer like Jim and his brother Lou—figures larger than life—to notice details like wildflowers or bees while climbing Rainier. For me, mountaineering was a form of physical and mental stress, a kind of rapturous torture. My reasons for subjecting myself to this struggle now seem distant, like thoughts from another life—motivations of a restless seeker determined to conquer summits at any cost. I was a young man at war with his own fragility, narrowly avoiding disaster several times, not through skill, but by sheer luck. The thrill of surviving with death so close was exhilarating, and the suffering felt sublime. But I’m done with that now.

I returned to the mountains because Willi’s enthusiasm for plants in high places commanded my attention. The light in his eyes when he spoke about climbing snowfields with an ice axe to find Cut-leaf Synthyris in bloom was as compelling as the alpenglow that illuminates the peaks at each day’s beginning, each day’s end.

I wish I could add decades to my life. With those extra years, I would find more friends like Willi who know that looking closely at the living world provides a path toward understanding where we are—and perhaps even who we are. I would deepen my study of bees and their imitators and learn about the other creatures of this Earth. We are all in peril, and we should appreciate the beauty of the world as sharply—and cling to life as fiercely—as a climber who steps above the void. Or a frog crossing a mountain pass.

In Upper Royal Basin, below Deception Pass, I peered into a tarn colored a surreal shade of turquoise and was startled to see a frog. High-altitude amphibians amaze me. Like flowers blooming in snowfields, ferns erupting from sun-scorched rocks, and bumble bees buzzing over alpine slopes whipped by freezing winds, frogs seem out of place in icy pools above timberline.

What are these creatures doing near mountaintops, far from the swampy lowlands where I thought they belonged? These frogs that hop to alpine heights don’t seem to be following the rules—rules that I was mistaken to believe were absolute. The world is a jumble, and the truths we cling to are merely threads to guide us through the tangled reality of life. Each thread, when examined closely, reveals something wondrous. This is one of the insights Willi helped me understand.

Before we delve into amphibians that live higher than the trees, let’s pause to consider a few questions that intrigued Willi. He wanted to know how this place that he loved had come into existence. What is a tarn? Why is the water in the froggy tarn in Upper Royal Basin such an eye-grabbing shade of turquoise? And why were this mountain basin, and Deception Pass above it, among Willi’s favorite places to look for endemic plants?

Royal Basin is a landscape shaped by alpine glaciers. Glaciers form when snow accumulates in such quantities that it compacts under its own weight and turns to ice. Driven by gravity, this ice slowly slides down mountain slopes. The glaciers scrape rock with the grit trapped beneath their icy bulk, sculpting mountains and widening valley floors. The glaciers that remain in the Pacific Northwest are mere remnants of once-massive ice sheets so extensive they influenced local weather by cooling the winds that swept over their cold surfaces. To envision the scale of these glaciers, consider Greenland, which is covered by ice nearly two miles thick. As Greenland’s glaciers melt, they will eventually leave behind a landscape like Upper Royal Basin.

As frozen rivers flowed along the present-day path of Royal Creek, they carved spacious basins. Today, waterfalls spill from one basin into the next, cascading down lava flows that solidified into erosion-resistant basalt ages ago. Upper Royal Basin is a cirque—a bowl-shaped depression scooped out of stone by glacial ice. This cirque is dotted with tarns, small mountain lakes formed by meltwater pooling in depressions left behind by the scouring ice. Tarns are tiny versions of the Great Lakes, vast meltwater bodies from the Ice Ages.

Silt from glacier-scraped stone spills into the waters of Upper Royal Basin, turning the tarns into fantastic hues: slate gray, chalk white, and vibrant blues and greens not found in any lake or sea. These dazzling pools resemble spilled paint beneath the clouds.

Upper Royal Basin is crisscrossed with moraines—masses of sediment carried by a glacier and deposited along its edges in lateral moraines and mounded at the glacier’s snout in terminal moraines. This earth-moving process creates a landscape reminiscent of mine tailings from industrial pits. But these moraines are not the result of human machinery. They are sculpted by nature’s own industry—the relentless work of ice and time, a testament to nature’s slow but boundless creativity.

Along one side of Upper Royal Basin, peaks known as The Needles pierce the sky. Tim McNulty, author of Olympic National Park: A Natural History, explained to me in an email that these mountains are “an upended late lava flow.” This event happened so recently in geologic history that erosion has yet to smooth the summits. Youthful and sharp, they are not yet weathered by erosion, not yet dulled by time.

How did this range rise? The Needles were born in volcanic violence when lava flowed. After the molten liquid solidified, geological forces tilted and uplifted this hardened lava flow. As a result, The Needles stand out prominently, their dramatic peaks a visible reminder of the region’s volcanic past and its tumultuous youth.

Willi, driven by the curiosity that he’d retained into old age, wanted to know more. How did the Olympic Mountains rise above the sea, lifting through time toward a world where snow falls in such abundance that the weightless flakes, in their countless trillions, press into ice, creating glaciers that sculpted the stone?

If you were to travel back 50 million years to where you now stand in Royal Basin, surrounded by bees, hoverflies, frogs, and endemic plants, you would find yourself floating in the sea. At that time, the West Coast was much further to the east. Over the ages, rivers deposited sand and silt into the ocean, and earthquakes spread this sediment across the seafloor. As sediment accumulated and was compressed beneath additional layers, sedimentary rocks like siltstones and sandstones formed.

Then fire enters the story. When the Earth’s plates shifted, a rift opened in the seafloor, leaking lava into the sea. The lava cooled to basalt. When plates collided, the soft sedimentary stone and the hard basalt were lifted millimeter by millimeter across millennia. This slow violence not only raised mountains into the sky; it also twisted the rocks. Strata were slowly warped. Rock layers turned sideways and were yanked apart and jammed back together, creating a jumble that keeps geologists busy trying to make sense of this glorious mess.

Sedimentary rocks in the Olympics are riddled with marine fossils, providing clues to the origins of these mountains that were once buried beneath the sea. Some of the basalt found atop these peaks displays rounded bulges, indicative of their marine past. This type of rock, known as pillow basalt, forms when lava cools rapidly underwater, creating its distinctive globular shape.

Press your fingers against the pillow basalt of a mountaintop, and you are touching fire from beneath the sea. To say that everything is connected is not merely a mystical claim from Eastern religions. It is a fact as solid as the rock beneath your hand.

Geologists know that patterns repeat, and they understand that the rocks of the world are endlessly recycled through time. They recognize that destruction and creation are closely intertwined. There is a strange resonance between sitting on the stone floor of a Buddhist monastery, listening to monks chant, and hearing geologists speak of stone. All will pass. Change is the only constant. Life is but a blink in the Buddha’s eye.

In Upper Royal Basin, your searching hand might discover a stone smoothed by a different force—ice, rather than fire. These rocks have been polished by glaciers, their surfaces bearing the marks of ancient ice ages. You can feel the striations and grooves, etched by glaciers as they dragged rocks across the landscape. Look closely, and you may also see what geologists call chatter: crescent-shaped gouges carved into the bedrock as stones were dragged beneath the ice.

Impermanence. Read about it in the sacred texts, read it in the rocks. Each glaciation event in Upper Royal Basin erased the traces of previous ice sheets, leaving only the record of the most recent glacier to traverse the land. It’s akin to a sand beach swept clean by waves—each new glacier carving its mark while the previous evidence is erased. The world is destroyed. The world is made anew.

The Pleistocene, the Ice Age epoch that began roughly 2.6 million years ago and ended around 11,700 years ago, did much of the major work to sculpt the Olympic Mountains. But the Little Ice Age, a brief period from roughly 1400 to 1900, saw glaciers advancing once more, shaping the Upper Royal Basin we see today. This glacial surge scoured much of the vegetation, bulldozing plants that had adapted to a land of wind and rock when the ice had previously retreated.

The geology of our world, with its eternal cycles of fire and ice, rarely gives living things a reprieve. All life is precious because it’s so precarious. Plants that bloom in harsh environments seem especially poignant.

Look beyond the polish and chatter of the rocks in Upper Royal Basin. Gaze past the sterile ice of the glacier draping the north face of Mount Mystery. Notice the valleys far below, green with mighty conifers. Glaciers help grow these forests that flow down to the sea. As rivers of moving ice pulverize stone, minerals are released into the soil. This enriched soil supports grasses that anchor and nourish the ground, paving the way for the towering trees of the Pacific Northwest—some of the tallest living things ever to have risen on this Earth. Though geology is a scientific discipline, it requires great leaps of imagination. Willi loved Upper Royal Basin and Deception Pass because they are playgrounds where the mind can wander and explore new ideas.

While meandering through Upper Royal Basin, you see boulders as big as houses lying in tumbled chaos across the land, what geologists call erratics. These rocks look out of place because they were transported by glaciers. Moved on a conveyor of ice, they were left behind when the glaciers melted. So say the sober geologists. More likely, the erratics were strewn by rowdy giants who stormed the hall of the mountain gods. When your mind roams this landscape, your imagination roars.

Watch a Cascades Frog leave a tarn in Upper Royal Basin and hop toward Deception Pass. This amphibian adventurer may be the Captain Vancouver of his species, leaving known waters to seek a new world, braving a mountain pass as he crosses to safety.

While you follow this frog on a journey among the mountain boulders, feel the glassy smoothness of glacial polish. Trace the rock striations with your fingertips. Touch an erratic. And consider that time may be circular, “not linear and progressive as our culture is bent on proving,” as Wallace Stegner writes in his novel Crossing to Safety. “Seen in geological perspective, we are fossils in the making, to be buried and eventually exposed again for the puzzlement of creatures of later eras. Seen in either geological or biological terms, we don’t warrant attention as individuals. One of us doesn’t differ that much from another; each generation repeats its parents, the works we build to outlast us are not much more enduring than anthills, and much less so than coral reefs. Here everything returns upon itself, repeats and renews itself, and present can hardly be told from past.”

But we exist only in the present. This moment is all we have—this moment with each other, and with the memories of those who have joined us on our journey.

Willi loved the geology of Upper Royal Basin, and he took delight in my story about a mountaineer frog embarking on an expedition from his home tarn to unknown heights. Yet, what Willi loved most were native plants, especially the endemic species in the alpine world of the Olympics that thrived in the most extreme conditions. Their vulnerability, coupled with their boldness and beauty, made his hands tremble when he touched them. Or perhaps that tremble was due to age, or maybe it existed only in my imagination.

We can never truly know what’s in the hearts of others. We can be deceived by people and deceive ourselves. But sometimes, we must be bold. We must step across the void and believe. I believe that Willi held thoughts as rare and beautiful as the blooms he sought in high places.

One of my fondest memories of Willi is when he showed me a carnivorous plant near a mountain creek. The eagerness of this white-haired man to point out a special plant was like the generosity of a child offering his favorite toy to a friend. Willi didn’t hoard knowledge, and he never showed off. He shared.

In the winter of 2022, Janet buried Willi at sea. She wrapped his body in weighted chains and released him into the deep. Until a heart attack ended his life in his seventies, Willi was hiking the deserts of southern Utah, sailing among the San Juan Islands, rowing, gardening, and botanizing in the mountains. Though he was a marine electrician by trade rather than a botanist, Willi taught me much about native plants. He showed me how gratifying it can be to nurture these rarities.

When Willi and Janet noticed that vulnerable Garry Oaks along roadsides near their home on Marrowstone Island had been sheared by brush cutters, they transplanted at-risk saplings to safer ground. To help restore the native oak population noted by Captain George Vancouver when he surveyed the area in 1792, Janet and Willi gathered acorns and grew them into seedlings. They raised these plants in pots and then transplanted them to wild groves.

When Willi died, to celebrate his life, around sixty Marrowstone islanders gathered in an oak grove planted by his hands. Janet wrote to me: “People walked or parked on the other side of the bridge, and as we dispersed, we were a laughing, chatting gaggle on both sides and in the middle of the road and bridge, looking very much like a geriatric group of trick-or-treaters. I laughed outright… They say that death creates life. That is true, but I think in the short run, death exposes and magnifies love.”

A few weeks later, Amy and I joined Janet in searching for oak seedlings she had planted with Willi near their home on Marrowstone. We bushwhacked through salal, scratching our skin on woodland roses. After making our way to the land’s end, where a bluff crumbles into the sea, we shoved aside dead wood with our feet and parted bushes with our hands, looking for oak leaves hidden among the undergrowth. During a half hour of searching, we located six scrappy little oaks. These modest plants may one day grow into giants.

Willi was a child at heart. He was also a giant of a human being. In the ship’s log from the final sailing voyage he and Janet took together, he wrote: “While hiking on the Ewing Cove trail yesterday, Janet found an origami packet that contained an earring. She later created a new use for the colorful paper. She refolded it, this time containing her wedding ring, and presented it to me with our morning bubbly. This provided an opportunity for me to slip it on her finger while gazing into her blue eyes and pledging another 25 years of devotion, respect, and loving companionship.”

Before Willi died, as I was leaving for a backpacking trip to Royal Basin, he shared a piece of advice: “Just before reaching the tarn in Upper Royal Basin, look left and find a route to Deception Pass.” Though I cannot recall the exact words this soft-spoken man used to describe Deception Pass, the light in his eyes convinced me to go.

Upon reaching Upper Royal Basin, I aimed my binoculars at the steep slope guarding Deception Pass and scoped its dangers. The route looked daunting. But if Willi loved Deception Pass and the plants it held, I knew I needed to experience this place for myself.

So up I went, following a faint path, climbing loose scree to reach an icy pool fringed with acid-green moss and yellow monkeyflowers. I continued higher, to where only the hardiest plants survive amid the cold, the wind, the stone. Blooms of Olympic Mountain Ragwort nodded like sunflowers. These tough beauties on the highest slopes had leaves like curled leather. I paused to stoop and study them, looking, smelling, and touching, as Willi had done when he encountered a rarity.

Willi taught me about plants. He also taught me to pay attention to what matters, to celebrate the people who mean the most to us, and to never take their love for granted.

After arriving at the top of Deception Pass and perching on a boulder with a view of Mount Mystery, life’s baffling path and Willi’s lessons were on my mind. This much I knew was true: My wife is my hero. Amy has the hardest job of anyone I know. She is a healthcare provider. When you are in your most vulnerable state, she will heal you. And then there’s her second job, arguably just as tough—putting up with me.

Amy is forever frustrated by my racing ahead on trails, my reluctance to pay attention to details worth noticing. I’m a poor student, but she is a patient teacher. Her description of a squirrel tipping forward on a branch, paws curled as it fell asleep in the sun, made me smile. I had been too stubborn to slow down and see.

I can list more birds than Amy can—knowing the names of things is in my job description as a naturalist. But Amy understands what’s important. She taught me to hear how a hummingbird’s beating wings change in pitch when its feathers are wet. She taught me to see a robin in our backyard as a worm would—like a T-rex stomping across the earth.

When you are in the presence of greatness, all you can do is take notes and learn. Amy’s imagination is vast, her heart larger than my own—a rare beauty among life’s cold and wind and stone.

A few years later, when I stood atop Deception Pass again, Willi’s bones lay at the bottom of the Salish Sea, shimmering in the distance behind me. As I gazed into Deception Basin at scenery reminiscent of Ladakh, my mind tunneled back to my days in the Himalaya.

I had been young and confused. Now, older and still confused, staring at Mount Mystery in the heart of the Olympic Range, the thought of a striving twenty-one-year-old seeking enlightenment from sages in Asia made me laugh. There are wise people in the mountains of India, to be sure. But wisdom is all around us, in the hearts of friends.

On Deception Pass, surrounded by slopes of broken stone riddled with blooming plants, no lesson gleaned from Eastern philosophy meant as much to me as Janet’s words: Death exposes and magnifies love.

The trick, I think, is to learn to love—without death prodding us to do so. Willi and Janet understood this. Amy understands it. And I think I am finally starting to understand it, too.

The goats are gone, helicoptered away from peaks where these grazers that brave the heights do not belong. Endemic plants of the Olympic Mountains are rebounding, spreading among the gravel and scree, regaining ground, blooming briefly in a riot of color each summer beneath the mountain sky, until fire and ice obliterate this world and build another.

As I scrambled down the slope, I couldn’t wait to get home and tell Amy about the plants on Deception Pass. Plants that grow nowhere else but in the Olympic Mountains, a range that rises a modest height above the sea. Plants that Willi taught me to love.

Stephen Grace, Naturalist Journeys’ 2025 Guide of the Year, leads tours worldwide and is an acclaimed author. He explores the Northwest’s natural history through snorkeling, paddleboarding, skiing, trail running, and backpacking.

Stephen Grace, Naturalist Journeys’ 2025 Guide of the Year, leads tours worldwide and is an acclaimed author. He explores the Northwest’s natural history through snorkeling, paddleboarding, skiing, trail running, and backpacking.

AdventuresNW

AdventuresNW