One warm summer morning in early August of 2005, a small group of grad students from Western Washington University and I gazed across a small lake at one of America’s most spectacular mountain views. The lake was indeed small, really a small tarn, its glass-like surface reflected a perfectly clear upside-down image of Glacier Peak, a gleaming white volcano of powerful symmetry. The mountain was framed in the foreground by spires of subalpine fir. That sunny morning, we had the place and the view to ourselves, rare for such an iconic viewing site. On the other hand possibly not entirely to ourselves. The day before, on the trail close to the lake, we saw bear tracks and watched a large black bear grazing huckleberries. Later, we spied the bear not far from our camp. Our efforts to raise our food out of its reach were laughable, but—full of huckleberries—it left us alone.

It is sobering to think that when the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, the population of the United States was 179 million and is now over 341 million. All outdoor recreation areas, wilderness included, are being hammered by users “loving them to death.”

Our purpose in being there, as part of a long backpack, was to ponder the ideas and realities of public land and wilderness. Image Lake is nestled on Miners Ridge in the Glacier Peak Wilderness, established by the Wilderness Act of 1964. This legislation created a National Wilderness Preservation System and set up a process that has led to nearly 112 million acres of American land being designated as Wilderness over the years. This seems like a lot of land, but it is only 2.7% of the contiguous United States.

The sublime alpine meadows we found ourselves in had once been slated to become an open pit copper mine, thus the name Miners Ridge. As we wandered the ridge, we picked up nuggets of colorful copper lying exposed in small streams.

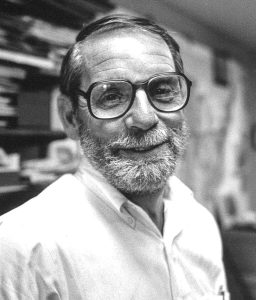

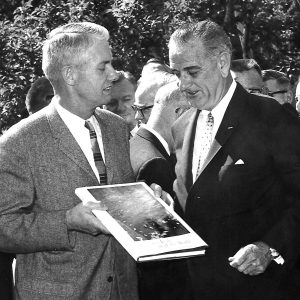

Thirty-five years before we visited, a renowned writer named John McPhee had visited this place along with a conservationist he profiled in a book titled Encounters With the Archdruid. David Brower, former leader of the Sierra Club and, in the late 1960s, executive director of Friends of the Earth, was the “archdruid” of conservation. He hiked to Miners Ridge with McPhee, a geologist and mineral engineer, Charles Park, and two University of Washington medical students. McPhee arranged this so he could record Brower and Park discussing the prospect of the Kennecott Corporation mining a large copper deposit under Plummer Mountain, a mile east of Image Lake, deep within the Glacier Peak Wilderness. The men spent several days hiking from Holden over Cloudy Pass to Suiattle Pass, across a flank of Plummer Mountain, then on to Image Lake and out the Suiattle River.

The jist of the discussion between Brower and Park was that Brower believed the area should be preserved for future generations as wilderness, whether or not it denied the present generation the benefits of the copper lode. Park argued that growing population pressure would ultimately lead to mining the copper, so why wait? Brower thought an open pit mine on Plummer Mountain would be a desecration, and Park insisted that it would not harm the view of Glacier Peak. As to wilderness, Park said, “I don’t agree with that concept of wilderness—to just take a big block of land and say you’re going to keep it for the future. I can’t see it.” Brower’s retort was, “Wilderness was originally a nice place to go to, but that is not what wilderness is for. Wilderness is the bank for the genetic variability of the Earth. We’re wiping out that reserve at a frightening rate. We should draw a line right now. Whatever is wild, leave it wild.”

In his account of the interaction of Brower and Park, McPhee brings out the complex nuances of the debate over wilderness. They were having this discussion a scant five years after the passage of the Wilderness Act, which congressionally established 9.1 million acres of wilderness, including the Glacier Peak Wilderness. Over the ensuing sixty years, considerable federally protected wilderness has been added, and no open pit mine has been dug on Miners Ridge. However, in the 21st century, the growth of the Wilderness System has slowed. Pressures on wilderness and all outdoor recreation areas have increased dramatically. It is sobering to think that when the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, the population of the United States was 179 million and is now over 341 million. All outdoor recreation areas, wilderness included, are being hammered by users “loving them to death.”

Since that morning, as we sat by Image Lake gazing at Glacier Peak and reading excerpts from McPhee’s book, I have encountered many who ask, “Why do we need wilderness anyhow?” For me, the Miners Ridge example provides the most definitive answer to this question. What if Kennecott had been permitted to mine there, digging a pit that would likely be at least half a mile from rim to rim? Road access to the mine would be essential to get equipment in and ore out, likely coming up the Suiattle River. The only other alternative would be up Agnes Creek from the Stehekin Valley or from Holden Village over Cloudy Pass, all of which would be huge developments slashing into wild and beautiful country.

After camping near Image Lake and discussing the issue, we continued to Suiattle Pass, camped there, took a day trip over Cloudy Pass to Lyman Lake, and then down Agnes Creek. Everywhere we went was gorgeous, with trails the only sign of human intrusion. We sat at the toe of the rapidly retreating Lyman Glacier and, on the descent of Agnes Creek, marveled at the ancient forest we experienced on our way to the Stehekin River.

A major industrial development in the heart of the Glacier Peak Wilderness would have more impacts than can be mentioned, but if there were road access into Agnes Creek, would the old-growth timber survive? Same for that in the Suiattle River Valley. I was astonished to learn that there had once been serious consideration of digging a tunnel under Cascade Pass to create road access to Stehekin Village. If there were timber to haul out of Agnes Creek, might that idea have been revived, outrageous as it seems, as a way to move logs out the Cascade River Road to the mill in Darrington? Where a road goes, so goes development, and this “what if” can go in many directions. Fortunately, the Forest Service, which administers the Glacier Peak Wilderness, conducted this exercise to discuss the impacts and raise many issues. Kennecott could see that permitting such a development would be difficult and even unlikely and slowly and reluctantly relinquished their mining claim, which is another long story.

What stopped them? A region rich in scenic and wildland value designated as wilderness. This example, for me, answers the question of “why wilderness?” If there had been no government-approved wilderness protection of this public land, the copper mine and all its related impacts, whatever they might have been, would be our reality. There would be a Glacier Peak Wilderness, but one bisected by industrial development. Historically, the idea of wilderness, as conceived by Aldo Leopold and others, emerged in response to the threat of rapid road-building and related development through public wildlands. Should there not be some places where wild creatures and those who love them have room to roam? The answer has been a resounding “Yes.” In a recent discussion of the Alpine Lakes region, someone from the Tulalip Tribes asked bluntly, “The animals have nowhere left to go. Where do you want them to go?” Where indeed?

But this story is not over. What Congress approves, Congress can disapprove. Only minor changes have been made to parts of the National Wilderness Preservation System once Congress has approved a wilderness, but this may not always be so. Consider the current situation where an incoming president shouts “drill baby, drill” and does so wherever there might be oil and gas. Charles Park said that the copper under Plummer Mountain would be needed and mined sooner or later. When might that be? Soon? David Brower often said that wilderness protection is never permanent, whether in a national forest, national park, or anywhere in the public domain. The fight to protect it will never end, and when a battle for protection is lost and wilderness developed, it is gone forever or, at the very least, will be very hard to rewild.

I enjoyed the good fortune of traveling to the Glacier Peak Wilderness many times, summiting the peak itself and enjoying it from every direction. Its power to impress and excite never waned. McPhee quoted Charles Park as saying, “How can you ruin a mountain like Glacier Peak? You can’t ruin it.” He added, “A mine would not hurt this country—not with proper housekeeping.” But you can, of course, ruin the experience of it from Image Lake. And “proper housekeeping,” whatever that entails, is very rare in the mining industry. Travel the American Southwest today, and confidence that this industry will ever practice “proper housekeeping” will be dashed.

The upshot of all of this is that there is a great need today to vigilantly protect all parts of the National Wilderness Preservation System and to enlarge it as much as possible. Several generations of persistent and sophisticated Washington wilderness advocates were very successful, and Congress in the 20th century designated much wilderness in the North Cascades, but will it last? We cannot be complacent and take it for granted because powerful interests will leap at every opportunity to challenge the restraint at the heart of the Wilderness Act. The prospect of such a challenge is imminent today. I encourage everyone who can to visit the Glacier Peak Wilderness, see what is at stake, and take up the cause of its protection.

John C. Miles climbed and hiked in the North Cascades for nearly 50 years. He also taught environmental studies at Western Washington University, taking students “into the field” as often as possible, and what a field it was. In retirement, living near Taos, New Mexico, he hikes and skis the Southern Rockies. His latest book is Teaching in the Rain: The Story of North Cascades Institute (2023).

John C. Miles climbed and hiked in the North Cascades for nearly 50 years. He also taught environmental studies at Western Washington University, taking students “into the field” as often as possible, and what a field it was. In retirement, living near Taos, New Mexico, he hikes and skis the Southern Rockies. His latest book is Teaching in the Rain: The Story of North Cascades Institute (2023).

AdventuresNW

AdventuresNW