With its extremely steep topography, the North Cascades is perhaps North America’s most rugged mountain range. Traversing along its crest is no simple feat. I am not talking about using hiking trails since they are predominantly in the valleys. I am talking about trekking on the ridges, staying as close to the crest as possible.

“Humility is directly correlated to survivability.” – Don Goodman

The first successful “traverse” was done in 1938 by members of the Ptarmigan Hiking Club. The ‘Ptarmigan Traverse’ extends from Cascade Pass, east of Marblemount, to near Glacier Peak and covers 35 miles while gaining and losing 11,000 feet in elevation. This traverse, considered a classic in the range, did not see a second party for 15 years. In the last 50 years, many other high-route traverses have been documented. Online blogs give voice to a devoted group of backcountry hikers obsessed with these routes, and I am one of those people.

Completing any of these high routes involves technical mountaineering skills, confident navigation, exhaustive planning, determination, endurance, and a bit of luck with the weather. The rugged terrain along these routes should not be underestimated.

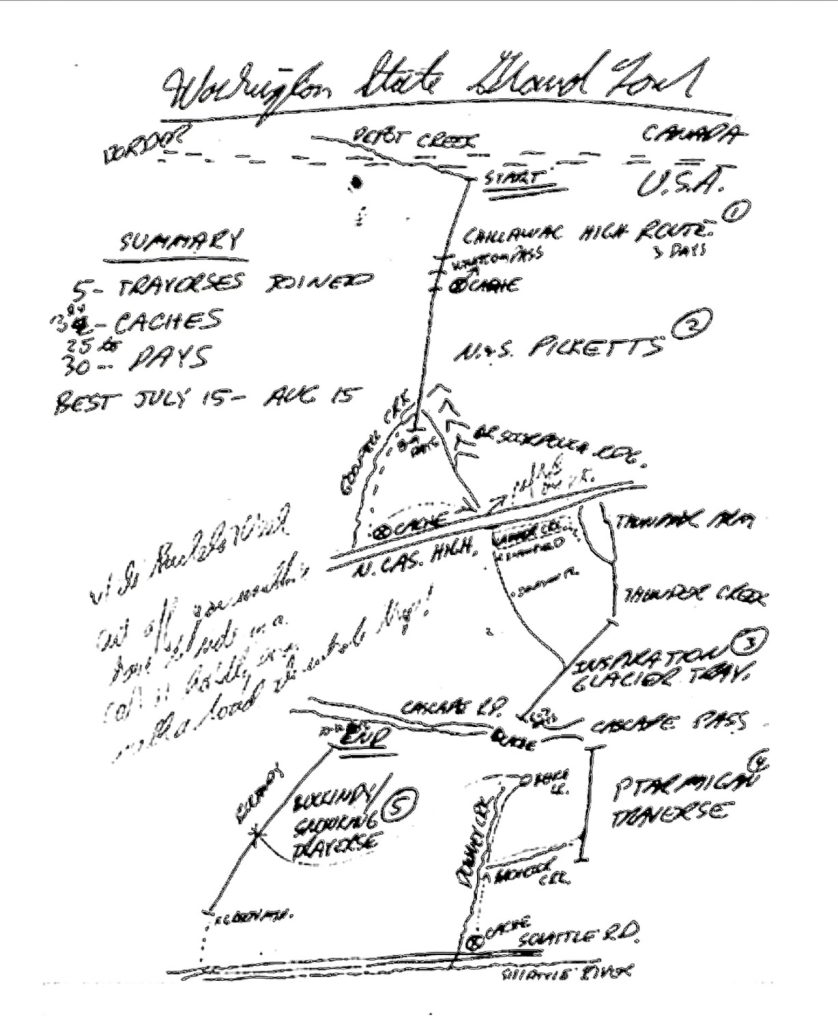

The jagged crest of the core area in the North Cascades National Park extends from just west of Ross Lake south into Glacier Peak Wilderness. There are four almost connecting named traverses along this remote crest, in order from north to south: The Redoubt Traverse, the Pickets Traverse, the Isolation Traverse, and the Ptarmigan Traverse. Together, they cover 125+ miles and almost 60,000 feet elevation gain/loss. That would be comparable to walking from Bellingham to Tacoma and climbing and descending Mount Everest twice!

In 1990, Don and Natala Goodman completed the first continuous trip linking these traverses into what Don called ‘The Grand Tour.’ On this 28-day trip, they summited 19 peaks. Another continuous linkup was completed in 2022 by Kaytlyn Gerbin and Jenny Abegg in under seven days! These two women used their trail running abilities and carried ultralight gear instead of the standard heavy backpacking equipment. Separated by 32 years, these two trips had remarkably different styles, reflecting some of the changing ethics in outdoor adventure travel.

I recently attended a presentation by Kaytlln and Jenny in the theater at Western Washington University in Bellingham. Joining me were the Goodmans. I was in awe of both couples’ accomplishments as well as their obvious mutual respect. I thought it would be inspiring to get their perspectives on these epic journeys made more than three decades apart, and they all readily agreed to answer my questions.

Sticking with a historical theme, I augmented my queries with “traverse perspectives” from mountaineering legend Lowell Skoog. Skoog, who has pioneered skiing many of the traverse routes, is the founder of the Northwest Mountaineering Journal and the chairman of the Mountaineers History and Library committee. Lowell’s quotes, shown in italics, are taken from Malcolm Bates’ classic book, “Cascade Voices: Conversations with Washington Mountaineers” (Mountaineers Books, 1992), in which he interviewed many iconic Cascade mountaineers.

You look at a bunch of mountains, but when you conceive of a route through these mountains, you don’t look at it the same way anymore. Now you see the route. The route is more than topography.

How did your identification of your route initially happen, and then how did it change how you view the mountains on the maps?

Don & Natala: It took a couple of decades to travel in the North Cascades to really “see” the possibilities. The maps were critical to the formation of the thought and plan. The release of the 7.5-minute (1:24000) USGS topos of the North Cascades allowed us a two-dimensional view at a scale and accuracy that greatly helped to facilitate cross-country travel in very rugged terrain. While the topography has much to do with the “route”, the actual “line” and a desire for a purity in connecting-the-dots, were also important.

Jenny: I love the transition that happens when you go from looking at a route on a map to experiencing it with your eyes and feet. I don’t think of myself as all that adept at the planning stage of things; it all feels like so much conjecture until you actually do the thing. Doing the thing is living it, taking an idea from a mere line to an experience of connection with the land, your partner, yourself. Now when I see that line that we traced across the mountains, it evokes all sorts of feelings and memories and a sense of love and oneness with Kaytlyn and the North Cascades. We’re so lucky to have gotten to live the line on the map.

The routes that people do are really an expression of their personalities.

How did your trip reflect your personality?

Don & Natala: The concept was clearly a boneheaded idea so in that sense, it did reflect our personalities.

Jenny: For better or for worse, I like to do most things quickly. And I love a good endurance challenge. If I was going to explore the North Cascades from top to bottom, this was going to be the way it was going to happen. I think I’m also fairly impulsive (also for better or for worse), so when Kaytlyn asked me if I wanted to do this journey with her, I barely thought before saying “yes.” It was an obvious yes.

I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that a big motivation in some of these traverses is that nobody has ever done this before.

Was that a motivation for you?

Don & Natala: Yes, there was some motivation to connect all these routes in a single push, which likely had not been done in that specific sequence prior to 1990. However, being first was not a prime objective.

Jenny: The North Cascades have been my backyard for as long as I can remember, and getting to know them in this way felt like such an incredible opportunity. I also loved the challenge of tapping into my skill set and fitness and doing it fast. It was such a cool idea that Kaytlyn had, and of course I wanted to be a part of it!

There is also the motivation that there is the element of the unknown, that you have to solve these problems.

What were the problems you had to solve? Which unknowns were most worrisome?

Don & Natala: With the exception of a few critical spots (“Pickel Pass” to Picket Pass, McMillian Cirque), the biggest challenges were mental. After several weeks, we became accustomed to this very basic existence in the natural world… completely being one with the natural world.

Jenny: I’d say planning for the trip posed more “problems” than actually being out there, but the inverse probably would have been equally true: If we (Kaytlyn, mainly) hadn’t planned so well, we would have faced a lot of difficulties out there. When we started at Silver Creek, we essentially knew the line we would be taking, which cut out so much decision-making while out in the high country. But, coming up with that line felt like a big thing to solve for…crowdsourcing ideas for getting through various sections, not having all the information to make good decisions, like, what will the terrain be like there? What will the snow levels be? How fast will we be able to travel? Etc.

I wonder about what it’s going to be like as most of the mysteries disappear. How will people find the kind of satisfaction that the old timers had exploring?

Don & Natala: Even with all the currently available “beta” I do not believe all of the mysteries disappear. There are just too many variables—weather, snow and, glacier conditions, etc. However, following a GPS course with a handheld may be a big takeaway. I cannot say for sure, as I have never used one in that context. Of course, one could leave those devices at home.

Jenny: As much as this journey felt exploratory, the reality is that we weren’t doing anything that hadn’t been done before. Hats off to those who did pioneer these areas, as they had to deal with so many more unknowns than we did. So, in many ways, this question is being posed to us: How will we find the kind of satisfaction that old timers had exploring? Because I can only know my experience, I don’t know what that type of satisfaction must have felt like, the satisfaction of discovering a place for the first time. But I will say that traversing the North Cascades with Kaytlyn left me feeling more satisfied than perhaps anything I’ve ever done in my life. Exploring the mysteries of a new landscape is surely an amazing experience, but so is exploring the mysteries of human potential, of ambition, of crafting a ridiculous plan—creating a game, really— and then carrying out that plan with our own set of chosen constraints, the rules to our game. Leaving behind “real life” for seven days and entering into a reality that offered the gift of effortless presence, 24/7, only me and Kaytlyn, and the task at hand. Getting to be so immersed in a challenge of our own making that yielded such a beautiful connection. Maybe you don’t need mystery in order to explore. Or better yet, maybe just because one person discovers a mystery doesn’t mean that it’s not still there for everyone else to have the satisfaction of discovering, too.

How did the high-route experience change you? How did the traverse experience compare in that regard with other outdoor adventures you have had?

Don & Natala: It reinforced what we already intrinsically knew. One of the most exciting and challenging mountain ranges on Earth exists right in our backyard.

Jenny: The high-route experience will probably always stand out as one of the highlights of my life. It was the perfect cocktail: an obvious line in our backyard that we hadn’t yet explored, a perfect partner, an amazing set of people supporting us, and health and weather all coming together at the same time. It showed me how cool it is that we have the ability as humans to create games for ourselves to play that can really elevate life to the next level, that playing these contrived games and working on something as a team can provide a level of connection and presence that is so distinct from what we typically allow ourselves in daily life.

The routes you took were through the most rugged section of the North Cascades. Were you ever humbled by the terrain, and if so, where?

Don & Natala: Oh gosh, on nearly a daily basis. Humility is directly correlated to survivability. As one moves through the mountain environment, changes can occur surprisingly rapidly. Snow and rock conditions (often relative to aspect), flora and fauna, exposure, current weather, etc., all these variables contribute to this sense of ruggedness and vulnerability.

Jenny: Every step of the way! The journey felt way too big for me to wrap my head around. So big that we had to take it in small sections. Not just day by day but section by section. Make it to that next pass. Just traverse this next snow slope. The terrain was always bigger than us. I’d say my biggest moments of doubt were around Mt. Challenger, when the weather was bad, and we were in the middle of a 16+ hour day, and the task at hand just felt too big. I remember sitting down to take my crampons off, knowing it was the only time I would be able to sit down all day and trying to relish in that small break. I enjoyed every second of that break, knowing that standing up meant that I wouldn’t get to sit down again for a very, very long time.

Each of you was joined by others on segments of your traverse. Explain why and explain how that altered the dynamics of your journey.

Don & Natala: While we knew it was going to be difficult to find someone willing to join us for the complete traverse, it was our goal to have at least one other person for each segment of the traverse. This goal was largely driven by safety, especially with respect to glacier travel. In fact, we initially had such companions lined up, but ultimately, for various reasons, only Juan Esteban Lira was able to join us for the Picket’s Traverse portion.

Jenny: This was an interesting part of Kaytlyn’s and my journey. We did the first four days (and the most technical part of the traverse) just the two of us and had such a great time. We fell into lockstep and just moved perfectly together. Our decision-making was so fluid and easy, and shared. When Michael and Steven joined us, it was fun to have new energy, but the route-finding decisions felt more complicated. We found ourselves deferring to them and getting off-route; it just became so much more complex to make decisions as four rather than two. I know we both missed the simplicity of just being two friends out in the mountains together. That said, by the end of the journey, our posse (which also included our photographer friend Nick and Kaytlyn’s husband Ely, who was a total logistics hero and made the whole thing possible) felt like such a family. I felt so incredibly supported and was in awe of how the group rallied around Kaytlyn and me and how excited they were about what we had done.

Can you imagine accomplishing what the other pair did on their traverses through the North Cascades?

Don & Natala: Slowing down is one thing; speeding up to Kaytlyn and Jenny’s speed is unfathomable. While one could argue in favor of a “smell-the-roses” pace, we are very impressed with the confidence they had in their ability to travel super light and super-fast. Moving quickly, especially in terrain such as climbing out of the McMillian Cirque, results in a very tangible safety advantage. In a way, their solution helps solve the “cannot break away” conundrum of the 21st Century. More power to you!

Jenny: Honestly, I don’t think what Kaytlyn and I did out there was any more impressive than what Don and Natala did just because we did it faster. The idea of spending 28 days out there and the logistics and heavy gear that would require is quite intense! And not having the ease of GPS that we did… I can imagine doing it, but what I can’t imagine is thinking it would be possible! I would have never gotten off my couch!

Traverse Timeline

1938 – Ptarmigan Traverse first completed in a 13-day trip

1953 – Second trip on the Ptarmigan Traverse

1979 – Jenny Abegg’s parents complete the Ptarmigan Traverse

1980 – Don Goodman completes the Ptarmigan Traverse

1981 – Ptarmigan Traverse is skied for the first time

1983 – Lowell Skoog and friends ski the Isolation Traverse

1985 – Lowell Skoog and friends ski the Picket Traverse

1988 – Ptarmigan Traverse is skied in 1 day by Lowell Skoog and friends

1990 – Don and Natala Goodman complete the Grand Tour in 28 days

1996 – The Abegg Family with Jenny (age 11) attempts the Ptarmigan Traverse and turns back. It is remembered as the “Death Hike,” and Jenny wished her parents had taken her to Disneyland instead.

2002 – The Abegg family completes the Ptarmigan Traverse

2020 – Kaytlyn Gerbin sets the Fastest Known Time for a female on the Ptarmigan Traverse (14 hours)

2022 – Kaytlyn Gerbin and Jenny Abegg complete the High Route in 6 days, 19 hours.

Embracing the uncertainty of true adventure has been a driving theme in Bob Kandiko’s lifestyle. Choosing “the new and the unknown” has not always been easy, but the rewards have been huge. He is planning more adventures.

Embracing the uncertainty of true adventure has been a driving theme in Bob Kandiko’s lifestyle. Choosing “the new and the unknown” has not always been easy, but the rewards have been huge. He is planning more adventures.

AdventuresNW

AdventuresNW

So very enlightening! Natala spoke about her adventures years ago. This brought them to light.