Story and Photos by Dave Mauro

This is the third installment in Dave Mauro’s Seven Summits series. In previous accounts, Dave was introduced to high altitude climbing on an unlikely ascent of Denali in Alaska, after which he successfully completed the classic trip to the roof of Africa, Mt. Kilimanjaro.

It is safe to say that the Russian people tend to be quite stoic.

We had observed this characteristic everywhere we went during our travels. This is perhaps the consequence of being the children of a generation that had little to smile about.

So it was notable when the passengers of our flight from Moscow to Mineralyne Vody spontaneously erupted in applause. The occasion of their joy was a safe landing. It is said that low expectations are the gateway to simple pleasures.

We boarded a van for the four hour drive to Azau, our base camp for the Mt. Elbrus climb. After summitting the highest peaks in North America (Denali) and Africa (Kilimanjaro), I was eager for this shot at the highest point in Europe.

Our route passed through modest towns and fields of Sunflowers. There were lean dogs and motionless burros. Shoeless children played with a kitten near a sad-faced old woman selling watermelons from a roadside stand. Incomplete walls protected incomplete homes. These towns all had stories we would never know. We were only passing through, Westerners here for some other purpose.

Azau is a village being built around a decommissioned gondola house at the base of Mt Elbrus. If there is a master plan for the development of Azau, no one has bothered looking at it. Structures have been started and then abandoned, their concrete and dangling rebar telling the forlorn tale of dreams that exceeded the fortunes of the dreamer. Our own hotel was a strangely modern structure featuring emerald green glass set into its white three story facade. Daylight was transformed into an eerie hue that fell heavy upon the simple furnishings within, a space left otherwise dark to allow the proprietors to conserve expensive electricity. I took to calling it Oz.

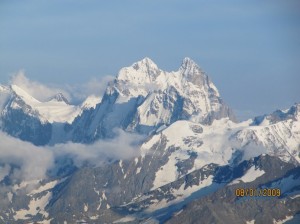

The high summit of Europe, Mt Elbrus, is located in the southern-most part of Russia, bordering Georgia as part of the Caucasus Mountains. Standing 18,510 feet tall, Elbrus is the fifth highest of the Seven Summits. Most climbers regard Elbrus as the “easiest” of the Seven. This is not unreasonable given the conveniences of a chair lift, gondola, and snow cat ride which combine to take a good bit of the climbing out of the climb. As well, Elbrus may be climbed without enduring even one cold night in a tent, such are the amenities that come with the mountain also being a ski resort. But all of this adds up to a head fake. Some climbers view Elbrus as the equivalent of summer camp, ignoring the requisite acclimatization and the violent unpredictable weather up high. As a result about ten of them die on Elbrus each year.

Our team included a young couple from New York, Ed and Swati. They were new to altitude climbing, but fit and enthusiastic. Dr Richard Birkill from my Kilimanjaro team was also along, largely because I had, for several weeks, taunted him with repeated text messages which called into question his courage and masculinity, quite often featuring the chicken tagline “Bocka Bocka Bocka”.

Our lead guide was famed climber Mike Roberts of Adventure Consultants. We were the lemmings – he was the sound of the sea. Mike is modest and soft-spoken, but his laugh is big, contagious, and somehow reveals the accent of his native New Zealand. Our team was rounded out by Alex, our local Russian guide. Alex had made a name for himself by soloing K2 the year before.

For the first several days we set out on various hikes designed to aid our acclimatization, each night returning to the comforts of Oz. Humorless Russian women served hot breakfast and dinners in the basement of our hotel. Our lunches were packed for us each day. There were comfortable beds and hot showers. I felt equal parts gratitude and embarrassment.

Our last day-hike took us up to 12,000 feet on Cheggett Mountain. This meant we were ready to leave Azau for high camp on Elbrus. The next day we loaded onto chair lifts which took the team up to a gondola station. We piled into several gondolas with our gear and completed the journey up to “The cubes” at high camp. The cubes are a cluster of steel boxes built with four bunks inside for sleeping. They are dirty and smelly, but they are heated and much more spacious than any tent. We moved into our cube then walked to the dining cube at our assigned time to eat.

The team had done well up to this point. We had completed most phases of acclimatization and felt good. The only exception was Swati, who had awakened an old foot injury and was experiencing a fair bit of pain. Alex suggested a Doctor look at Swati’s foot. When we pointed out that Richard is a Doctor, Alex shook his head “No No No! Professional Doctor!” he asserted. Richard was a good sport, allowing the group a laugh at his expense. But the next day Swati’s foot kept her from completing the final acclimation climb to the Pastukhova Rocks at 15,000 feet and her summit dream fell into question.

We took a rest day at high camp, working on our snow skills and trying to buy some time for Swati’s foot to improve. But when we woke at 1 a.m. to leave for the summit the following day, it was clear Swati would not be leaving with us. Ironically, her troubled foot was not the cause. She had contracted some form of intestinal bug and been up vomiting much of the night.

Swati had done everything right; put in the training, bought the expensive gear, hired the best guides, suffered through her foot problem, and endured the chronic discomforts of altitude acclimatization. But in the end this would not be her day.

It’s a hard thing to see someone’s dream come apart. We all felt terrible for Swati. Ed offered to give up his own summit dream to stay behind and care for her, but she insisted that he press on with the climb. Mike and Richard provided medications. Arrangements were made to have her taken down to Azau where the comforts of Oz would provide some relief. She smiled and bravely waved goodbye to us.

We geared up and boarded the snow cat for the ride that would take us back to where our climb had left off two days prior at 15,000 feet. By 2:30 a.m. we were stepping off the snow cat, crampons on, and starting up the first grueling pitch, a steep incline 1,200 feet up the west flank of Elbrus. We made decent progress for the first hour, but then our pace started falling off. The wind had picked up and it became increasingly difficult to stay warm. From my place at the back of the team I could see that Richard seemed to be working much harder than the rest of us. Something was wrong. The temperature was down to – 5 degrees Fahrenheit. This was not extraordinarily cold, but with the oxygen-diminished air the physiological effect is amplified. Mike called for a break and suggested we put on our heavy summit parkas, over pants, balaclavas, and mittens. I dug each from my pack and put them on, feeling immediately better. We continued on, our bodies warmer, our pace still slow. After 30 minutes I noticed Richard was duck-footing his right foot outward and pushing off of it to step forward and uphill with the left. I called for the team to stop and climbed up to Richard. Pointing out what I had noticed, I urged him to not squander his energy with such an inefficient practice.

We began the second pitch, a long steep traverse winding northward. Dawn broke, but we were still on the dark side of Elbrus. It occurred to me that our problems with the cold would be solved if we could traverse out of the mountain’s shadow. Then Richard suddenly stopped. He, Mike, and Alex had a discussion. By the time I climbed up to them it had been decided that Richard would take a dose of Diamox to stabilize the altitude effects. He had been talking about turning back. “We are trying to persuade him to continue on,” Mike said, having seen climbers work through such conditions many times, believing Richard might do the same.

It was hard to say how much of Richard’s problems were the result of altitude, hypothermia, or issues of general fitness. On some level, each factor appeared to be contributing. But there was something else. “I have a bad feeling about this,” Richard said. Back in Moscow he had shared with me a grim premonition that had come to him as he said goodbye to one of his daughters. This foreboding was now consuming his thoughts and still more precious energy. Hearing this, Mike asked if Richard would feel better continuing on if they were roped together, a technique called “short roping.” Richard said he would, so Mike started rigging the line. At some point Mike looked at Ed and didn’t like what he saw. “Ed,” he said,” you’ve just been standing there and you still don’t have your over-pants on. I’m starting to question your judgment. Don’t fade on me, buddy. Put those over-pants on now.”

Then Mike turned back to Richard, who had a new problem. With all of the standing around his left foot had gone numb. “Right, we will remove the boot and warm the foot,” Mike said, instructing Richard to lay on his back and place the afflicted foot under Mikes upper layers, against the bare flesh of his stomach. I asked what I could do to help and was handed the inner liner of Richard’s boot. “Keep this somewhere warm,” Mike said. I stuffed it under my parka.

Then I glanced back at Ed and noticed he was impossibly tangled up in the process of putting on his over-pants, the crampons of his right foot piercing them in three places. I backed his foot out and opened the leg zippers completely. Then I carefully guided each foot through. Things were becoming worrisome.

The team plodded on, chasing the edge of the shadow and the hope that our climb would emerge stronger in the light of day. We passed into the sun forty minutes later on a section of the traverse that flattens out. The combination of warmer conditions and a rest for our legs turned everything around. As we paused to hydrate, I turned to Ed. “We will stand on top of this &#!*% before the day is out!”

“Yeah,” he agreed, “I think we will.”

By the time we reached the east side of the saddle we were all removing layers and applying sunscreen. Richard shed his pack at the base of our next pitch, a steep climb rising 1,600 feet from the saddle to the summit plateau. He was still struggling but seemed to have reached down deep and found what it takes to carry on when most of you wants to cash in.

“And now, dear friends,” Alex called out, “the final forty meters! Most difficult part of climb.” Not only the steepest grade we had seen, this section also menaced climbers with a sheer 2,000 foot drop off on one side. There could be no mistakes. For the next forty minutes we methodically scratched our way up the narrow catwalk at the top of the pitch and onto the summit plateau. Again we rested, hydrated, opened the zipper vents on our clothing, and applied more sunscreen.

We had been climbing for eight hours and had gained almost 3,500 vertical feet. Now, from where we sat drinking Gatorade, we could see the final rise of fifty feet to the summit on the far side of the plateau. As we took those final steps, the realization of what we had accomplished settled on me. There were hugs and photos. We all said how much we wished Swati was there. I called my mother and my love, Lin, on the satellite phone. Then I released my brothers ashes to the Russian wind.

This is the third in a series of seven stories by Dave Mauro, each describing the ascent of one of the “Seven Summits”; the highest points on each continent. Next up: Aconcagua

Dave Mauro is a longtime Bellingham, WA. resident. By day he works as a financial advisor at UBS. By night he is an improv actor at the Upfront Theatre. Now and again, he travels the world with the goal of climbing the highest summit on each of the planet’s continents. Follow his quest at www.AdventuresNW.com

His blogs, photos and videos are also available at https://sites.google.com/site/davidjmauro/.

AdventuresNW

AdventuresNW