Lily Point is located at the southeast corner of Point Roberts with the waters of Georgia Strait on one side and Boundary Bay on the other, just a half-hour drive from Vancouver, B.C.

To get there from Bellingham, you must cross into Canada and then again cross the border to enter Point Roberts, U.S.A. When Canada and the United States signed the treaty in 1846 establishing the international border at the 49th parallel, they nipped off Point Roberts and left it as a dangling piece of the United States.

“People never go wrong protecting the land” – Lummi Chief Bill James (Tsilix)

The story of Lily Point begins some 15,000 years ago, when retreating glaciers left the sand and gravel deposits that formed Point Roberts on the edge of the Pacific Ocean. The highest reach of this glacial deposit, some 200 feet above the sea, is Lily Point. As you will see, these sand and gravel cliffs played a key role in the story of conserving this special place.

Ecologically, Lily Point is a dynamic place. Nutrient-filled currents sweep reefs and tidelands; mature riparian forests provide shade, bird perches, and copious insects; and eroding cliffs supply sand and gravel essential for spawning fish and beach replenishment. These processes are essential to the health of Puget Sound. Orcas patrol the Strait of Georgia, salmon skirt Lily Point on their way to their spawning grounds in the Fraser and Nooksack Rivers, bald eagles scour the beach, and great blue herons stalk the tidelands. Waterfowl and shore birds flock to Boundary Bay, a critical stopover in the spring and fall migrations for 50 different species of shorebirds numbering in the hundreds of thousands. The Nature Conservancy lists Lily Point as a “Priority Conservation Area” because of the site’s exceptional and regionally important ecological values.

During a June low tide, Gordon Scott, my essential partner in the Lily Point project and Whatcom Land Trust’s first conservation director, and I saw nearly 100 eagles on the beach at Lily Point, many atop large, exposed rocks. On another rare minus-4 tide day, my wife Dana and I took a rubber boot walk with marine biologist Bert Webber and his wife Sue on the long spit that extends out from Lily Point. The array of intertidal marine life was stunning. The density of squirting clams felt like we were walking in rain coming from the ground up. On the usually submerged island at the far end of the spit, we could see members of the Lummi Nation harvesting bounty from the sea as they had for centuries.

The history of Lily Point attests to its fecundity. Archeologists date human occupancy back at least 9000 years. In 1791, a Spanish explorer reported “an incredible quantity of rich salmon and numerous Indians” at Lily Point. A year later, Peter Puget, sailing with Captain George Vancouver, described a seasonal village at Lily Point with houses for 400 to 500 people, where the Coastal Salish peoples had maintained their primary reef net fishery for centuries, harvesting salmon as they passed close to shore while rounding Lily Point. The Native People called this place Chelhtenem, which means “hang salmon for drying.”

An 1881 newspaper reported that three reef nets took 10,000 fish in six hours. In 1889, 16 Native reef nets were in operation here, and a single net would catch as many as 2,000 fish a day.

Chelhtenem also served as a final resting place for many Lummi elders.

A Refuge of Abundance

For centuries, Chelhtenem was a center of traditional salmon culture and a place of great spiritual power. Each year, Lummi ancestors performed their most important First Salmon Ceremony here to assure the annual return of the fish. The Ceremony honored the returning salmon and directed them into the reef nets. The bones of the first fish “were carefully returned to the sea where the fish regained its form and told other salmon how well it had been treated, thus allowing the capture of other fish and insuring a return the following year.” (Application for inclusion of Chelhtenem in the National Register of Historic Places as a Traditional Cultural Property, 1992). Chelhtenem was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1994 as a site of national cultural, Traditional, and Spiritual Significance, the second place in Washington State to receive such a designation.

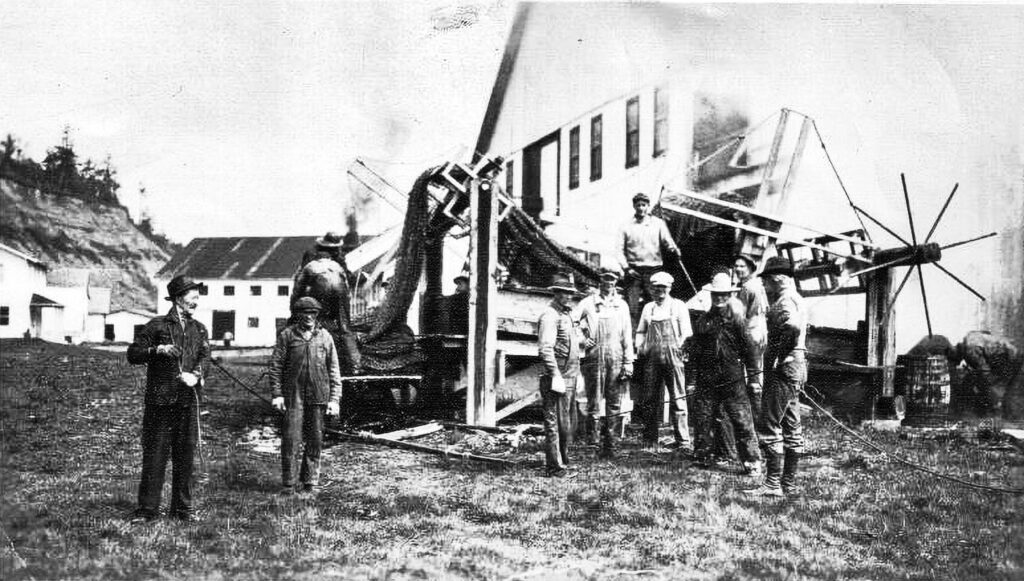

In the late 19th century, non-Indian fish traps displaced traditional reef nets. Alaska Packers purchased a year-old cannery at Lily Point in 1884. A photo of the cannery includes the almost impenetrable density of fish traps adjacent to the cannery. A picture of the “Tar Gang” shows the men charged with running the hemp fish trap nets on a giant wheel through a vat of tar to prolong their serviceability. The cannery was abolished in 1917, leaving pilings and debris still visible today. The pilings have been left in place to avoid causing more pollution by disturbing them.

Eventually, a developer acquired the property to construct a regional recreational resort with condominiums, a golf course, and 74 residential lots on the uplands and a clubhouse on the vegetated flatland between the cliffs and the beach. For reasons unknown, the developer let its permit expire and put the property on the market.

In 2007, with the support of the Lummi Nation, Whatcom Land Trust secured the right to buy this spectacular 90-acre marine shoreline property with 40 acres of tidelands for $3.5 million. By whatever mix of spiritual and ecological powers, Lily Point remained a place of prolific natural productivity just as it was when Salish people invoked higher powers to ensure the return of the salmon to Chelhtenem.

Undaunted by a price tag, the likes of which the Land Trust had never even dreamed of, we worked with a remarkable coalition of partners to raise the money to make the purchase. The fundraising breakthrough came in August 2007, with a $1.75 million grant from the State Estuary and Salmon Restoration Program (ESRP), administered by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife – over 23% of the funds available for 73 applicants.

When Gordon Scott and I, two liberal arts majors, submitted our grant application to the ESRP technical review committee, we downplayed Lily Point’s eroding sandy cliffs as the only shortcoming in the otherwise extraordinary ecosystem. A few days later, we got a call from the Nature Conservancy representative on the review committee letting us know that the eroding cliffs are a primary ecological feature of Lily Point. Currents carry sand from the cliffs to the beaches of Boundary Bay, supporting this critical stopover point for hundreds of thousands of migrating shorebirds. The regular addition of fresh sand is essential to the reproduction of tiny beach organisms that the shorebirds depend upon to fuel their seasonal migrations.

We immediately amended our application.

Paul Cereghino, ESRP Program Manager, foresaw the funding success: “Whatcom Land Trust’s marathon effort to acquire Lily Point combines protection of vital ecosystem processes and diverse wildlife habitat, a vivid cultural history, and local community engagement. We were pleased to see it at the top of our technical ranking.” In the $1.75 million grant commitment letter, Tim Smith, Program Director of the Puget Sound Nearshore Partnership, wrote: “Lily Point is one of the most culturally, scenically, and ecologically rich properties in the greater Puget Sound region. Lily Point’s healthy reefs, rocky tidelands, sandy beaches, mature marine shoreline forests, and two extensive feeder bluffs contribute substantially to the vitality of the South Georgia Basin.”

With enthusiastic support from Whatcom County Executive Pete Kremen, the County Council added $600,000 from the County Conservation Futures Fund to support the purchase, and the Washington Department of Ecology contributed $550,000.

“It’s probably one of the very few remaining properties in all of Puget Sound that possesses so many undisturbed environmental qualities,” said Richard Grout, Ecology’s Bellingham Field Office manager. “We thought it was an exceptional opportunity to help them acquire an exceptional piece of property. That kind of thing in Puget Sound is almost gone. This is a jewel.”

In addition to $250,000 of its own funds, Whatcom Land Trust raised nearly $400,000 in private donations from the U.S. and Canada. Symbolic of the shared responsibility for protecting this incredible marine resource, the two most significant private donations came from each country. With funds in hand, Whatcom Land Trust purchased the 140-acre Lily Point property in early 2008 and deeded the property to Whatcom County to create the Lily Point Marine Reserve.

The Land Trust retained a legally binding conservation easement that first and foremost protects “the ecological functions and processes, environmental attributes, and wildlife habitat of the Property” in perpetuity. The easement goes on to state that “Secondary purposes are to preserve the aesthetic qualities of the Property and permit passive, nature-oriented public access that does not significantly infringe upon the primary purpose of the Conservation Easement.”

Celebration

It was raining at Lily Point on June 4, 2008, yet over a hundred and fifty people gathered from the Lummi Nation, Canada, and the U.S. to celebrate and give thanks that Lily Point was protected forever. The rain stopped. The sun broke through the clouds. One of the lowest tides in decades revealed the splendor of Lily Point’s intertidal life and laid bare the rocks where dozens upon dozens of eagles stood sentry. A delegation from the Lummi Nation came to bless the conservation of Lily Point with drumming and song, including the Traditional Lummi Chief Bill James (Tsilix) and the head of the Lummi Cultural Department, James Hillaire (Tallawheuse), known to everyone as “Uncle Smitty.“

Chief James addressed the crowd: “Thank you for all the work you have done protecting the land, protecting our ancestors, protecting the grandparents, the great grandparents, and all of the elders that have gone before us. It’s really hard to express how much we appreciate them being protected now. Our ancestors can now rest in peace knowing that this place will never be developed.”

Henry Cagey, Chairman of the Lummi Indian Business Council, sent his thanks: “On behalf of the Lummi Indian Business Council and the Lummi Nation, we’d like to extend a heartfelt thank you “Hy’shqe”to the Whatcom Land Trust for protecting one of the traditional territories of the Lummi people. Lily Point has been a refuge of abundance for the Coast Salish People ….”

Washington’s Governor Christine Gregoire commemorated the day in a letter read to those gathered at Lily Point: “Today, we celebrate the Whatcom Land Trust’s acquisition of Lily Point, a breathtaking 90-acre shoreline property, with 40 acres of tidelands …. This gem and its biological and historical richness will be preserved for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Wearing a traditional cedar bark hat, Uncle Smitty spoke with drum in hand: “I am very honored to be invited to this gathering and to recognize the work that has been done to preserve our homeland. We hold our hands up to all of those involved in the preservation of this area. We share with you the desire that this place not be disturbed. A lot of our ancestors are buried here. This is what we want to protect–their resting place… and once again from our hearts to your hearts, we thank you.”

Richard Grout, Manager of the Washington State Department of Ecology’s Bellingham office, referred to the Olympic Pipeline/ Whatcom Creek disaster that had killed three boys and resulted in the largest penalty fine in state history. “One of the commitments I made to myself was that we would use that money for things that would be a lasting memorial to those kids and to that whole event. Somebody said earlier today that the only way you really protect a place is to buy it…working with the Land Trust has given us the opportunity to do that.”

As Tim Smith of the State Fish and Wildlife told the crowd that day: “When I was informed that Whatcom Land Trust needed 1.75 million dollars, being a good steward of the state resources, I summoned Paul Cereghino (Director of the Salmon Restoration Program) and said to him, ‘Paul, are you out of your mind? Last year, we got 2.5 million dollars for all of Puget Sound, and this year, you are asking $1.75 million for Lily Point. I need some confirmation here.’ Paul provided the scientists’ technical reviews and supporting documents, and said to me, ‘You’ve got to sign this. If this is really about saving and restoring the most important, the best places in Puget Sound, sign the check.’ And so I did, and so we’re here. And I could not be more pleased.”

As the sun, moon, and earth aligned to lower the tide on that memorable day in June 2008, the permanent conservation of Lily Point brought together cultures and countries, ecological and human health, private and public interests, past and future, hopes and dreams.

In a few simple words, Chief James summed up the accomplishment: “People never go wrong protecting the land.”

Forty-one years ago, Rand Jack helped create Whatcom Land Trust and continues as an ancient board member. He loves trees and birds and making birds out of former trees. He wonders what kind of world we are leaving to our grandchildren and the other creatures on this earth?

Forty-one years ago, Rand Jack helped create Whatcom Land Trust and continues as an ancient board member. He loves trees and birds and making birds out of former trees. He wonders what kind of world we are leaving to our grandchildren and the other creatures on this earth?

AdventuresNW

AdventuresNW

Loved reading about the Acquisition of Lily Point. I have always felt that it was a spiritual place and a very important place for the Lummi nation. I have lived here for 9 years and can never get over the beauty of Lily Point.

Whenever we visit Lily Point we can feel the history of that land, seeing those pilings gives you a sense of the huge community that thrived there. It truly is a magical place. Please note the article states that Lily Point is on the South West corner of Point Roberts, but it is actually the South East corner.